Its the end of the Australian summer now, and the entomofauna here in Canberra is at its peak! The pitchers are quickly filling up with flies and hosting a range of other insects that aren’t necessarily caught.

Unlike North America and Europe, our season starts very late (February) and reaches its peak through March and April. This would be like having the field season in Vancouver starting in August and reaching its peak in September-October. In reality, Vancouver reaches its peak around July (midsummer)! This grapevine moth (Phalaenoides glycinae) was not caught by this S. leucophylla x psittacina, but it fed at a few pitchers before it departed. This and similar Agaristine moths are flying around in some numbers now.

A great part of growing Sarracenia outside is the number of insects they catch themselves. At the moment, there are loads of blowflies hanging around the pitcher plants, which means a steady stream of flies falling into the pitchers. Every few seconds you can hear the high pitched buzz of the most recent victims. If there is a breeze blowing the pitchers around, the buzz is almost non-stop!

Interestingly, these blowflies almost seem to be using the trays of pitchers as a lek. I’ve noticed most flies (at least initially) perch on top of a pitcher lid and busy themselves intercepting other flies, presumably in search of a mate.

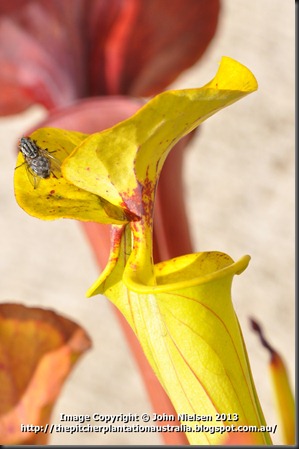

But it doesn’t take long for the flies to discover the nectar and start feeding. And once they get a taste of Sarracenia nectar, there’s no going back. Note this blowfly’s proboscis is busily probing away at the nectar glands along the edge of this S. flava lid.

Being rather cocky creatures, these blowflies flit from pitcher to pitcher, drinking as much nectar as they can find.

Here we see a blowfly cleaning its feet after having a good feed. Insects are actually rather clean creatures, and spend a lot of their time grooming themselves.

But one thing insects can’t efficiently clean themselves of is the neurotoxin coniine that occurs in the nectar of S. flava. After a few pitcher visits, the flies start to become too cocky, and venture closer and closer to the danger zone – the vertical throat of the pitcher!

This fly is really living very dangerously right now!

Amazingly, this fly reversed out of the pitcher and fed briefly on the hood of this pitcher. But then, faster than I could catch on camera, the fly lost its foothold and disappeared into the pitcher. There was a fly there a split second before, honest!

A few people have got in touch after my post on fertilising Sarracenia and asked just how necessary it is to fertilise. The answer is it isn’t, especially if your plants are catching insects. Fertiliser is more-or-less cheating: giving your plants extra nutrition to boost their growth. It is rare for Sarracenia not to lure and catch insects outside, especially if you grow lots of plants together.

In fact, Sarracenia often catch so many insects that the release of nutrients from the rotting bodies burns the pitcher! This appears as brown or dead patches on the pitcher tube. Pitcher burn is a major reason why Sarracenia have to produce new traps through the year – the old ones fill up too fast and loose their effectiveness.

Pitcher rot often causes pitchers to look strange. This S. alata is wilting off at the top, much in the same way it would if the rhizome were dying. In this case, it is just pitcher rot, but it caused me to do a double take when I saw it from a distance!

And to close – how the plants looked as of today:

Happy growing!